Iranian Center Site

ENGLISH PAGEIranian Center Site

ENGLISH PAGELife of Rumi

|

I silently moaned so that for a hundred centuries to come, (Divan, 562:7) |

The name Mowlana Jalaluddin Rumi stands for Love and ecstatic flight into the infinite. Rumi is one of the great spiritual masters and poetical geniuses of mankind and was the founder of the Mawlawi Sufi order, a leading mystical brotherhood of Islam.

Rumi was born in Wakhsh (Tajikistan) under the administration of Balkh in 30 September 1207 to a family of learned theologians. Escaping the Mongol invasion and destruction, Rumi and his family traveled extensively in the Muslim lands, performed pilgrimage to Mecca and finally settled in Konya, Anatolia, then part of Seljuk Empire. When his father Bahaduddin Valad passed away, Rumi succeeded his father in 1231 as professor in religious sciences. Rumi 24 years old, was an already accomplished scholar in religious and positive sciences.

He was introduced into the mystical path by a wandering dervish, Shamsuddin of Tabriz. His love and his bereavement for the death of Shams found their expression in a surge of music, dance and lyric poems,`Divani Shamsi Tabrizi'. Rumi is the author of six volume didactic epic work, the `Mathnawi',called as the 'Koran in Persian' by Jami, and discourses,`Fihi ma Fihi', written to introduce his disciples into metaphysics.

If there is any general idea underlying Rumi's poetry, it is the absolute love of God. His influence on thought, literature and all forms of aesthetic expression in the world of Islam cannot be overrated.

Mevlana Jalaluddin Rumi died on December 17, 1273. Men of five faiths followed his bier. That night was named Sebul Arus (Night of Union). Ever since, the Mawlawi dervishes have kept that date as a festival.

The day I've died, my pall is moving on -

But do not think my heart is still on earth!

Don't weep and pity me: "Oh woe, how awful!"

You fall in devil's snare - woe, that is awful!

Don't cry "Woe, parted!" at my burial -

For me this is the time of joyful meeting!

Don't say "Farewell!" when I'm put in the grave -

A curtain is it for eternal bliss.

You saw "descending" - now look at the rising!

Is setting dangerous for sun and moon?

To you it looks like setting, but it's rising;

The coffin seems a jail, yet it means freedom.

Which seed fell in the earth that did not grow there?

Why do you doubt the fate of human seed?

What bucket came not filled from out the cistern?

Why should the Yusaf "Soul" then fear this well?

Close here your mouth and open it on that side.

So that your hymns may sound in Where- no-place!

Schimmel, Annemarie.Look! This Is Love: Poems of Rumi.

Boston, Mass.: Shambhala Publications, 1991

PART ۱ : BEAUTIFUL IRAN

PART ۱ : BEAUTIFUL IRAN

Uramunat- Azerbaijan- North western Iran

-

armenian-church-Azerbaijan- North western Iran

a-serene-lake-in-guilan-northern-iran

-

aali-gaapou-isfahan-iran

-

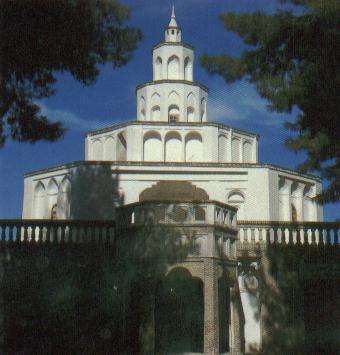

arg-e-kola-farangi-birjand-iran

-

asalem-khalkhal-Azerbaijan- North western Iran

-

bagh-e-eram-palace-gardens-shiraz

-

chahar-bagh-avenue-isfahan

-

chehel-sotoun-palace-pavilion-isfahan

-

cottage-in-northern-iran

-

ferdowsi-toos-khorasan-iran

-

kohgiluyeh-boyer-ahmad-province-iran

-

lahijan-guilan-province-iran

-

latian-lake-near-tehran

-

izeh-south-western-iran

-

layalestan-gilan-northern-iran

-

mansion-in-mazanderan-northern-iran

-

marble-palace-tehran

-

margoon-waterfall

-

museum-of-fine-arts-tehran-iran

-

niasar-isfahan-iran

-

Lake Urmia-Azerbaijan- North wester

IN

PART 2: BEAUTIFUL IRAN

Oh... I really missed my beautiful country! Hey... Good old days...

Arabic Maps of the Persian Gulf

information : Arabic Maps of the Persian Gulf

|

| ||

Map of the Islamic Empire, Sobhi Abdul-Karim, Cairo, 1965 |  Arabic Map of Saudi Arabia, Map Art USA, 1966 | ||

Arabic Map of the Persian Gulf, Date Unknown |  Islamic Map, Kabul, writing by Mohammed Hosein Haikal, 1968 | ||

Arabic Map of the Persian Gulf, by Arab scholar Dr. Hassan Ibrahim Hassan from his book "Political History of Islam" in Arabic. Published by Hejazi Printing House, Cairo, 1935 |

history of the persian gulf

history of the persian gulf

The Persian Gulf is a unique geographical phenomenon whose role in human affairs began in remote antiquity and has continued to our own day. Traditionally, this role was due to the place it occupies as an avenue of cultures and trade; today, as the site of a resource vital not only for the inhabitants of the countries along its shores but for much of the modem world. The Persian Gulf's unique geo-strategic position further enhances its present importance.

The earliest recorded civilizations appeared near its shores some five millennia ago, when the kingdoms of Elam and Sumer blossomed at the head of the Persian Gulf in what is today south-western Iran near the estuaries of the rivers Tigris and Euphrates. There is evidence that they and their successors, the Assyrians and Babylonians, had relations with maritime principalities along the southern coast of the Persian Gulf, and that trade in precious commodities grew. By the time the Roman Empire became the great consumer of Oriental luxuries such as spices, gems and pearls, the Sinus Persicus functioned as one of the principal routes by which this commerce moved. The spices and gems came from India and the Orient further east; the pearls chiefly from the Persian Gulf. Indeed, pearls were the famous luxury item exported from there ever since antiquity until, by a curious coincidence, they were replaced by oil in the first half of the 20th century.

Even before this flow of Roman specie exchanged for Oriental luxuries began, a political transformation had occurred in the entire area. The last great Mesopotamian kingdom of Babylon had been conquered by the Persians, whose earliest historical kingdom, that of the Achaemenids, spread its rule over much of the Middle East. They and their successors, the Seleucids, Parthians and Sassanians, created an empire which intermittently controlled the Persian Gulf. They sent expeditions and acquired coastal regions also on the Arab side, a process that in turn stimulated mutual interest and movement of populations and occasional settlement and dominance of some Persian segments by Arabs. This Arabo-Persian maritime community asserted itself to an almost legendary degree after the foundation of the Islamic Abbasid caliphate at Baghdad in the middle of the 8th century. Masters of a huge empire, the caliphs and their prosperous elites became consumers of Oriental luxuries. Their own subjects, Persian and Arab, were the merchants and mariners who now brought an ever growing range of commodities not only from India but even from China. Then as now, the romantic story of this maritime trade fired the curiosity and imagination of the public, and the adventures of Sindbad the Sailor became an indelible part of the Thousand and One Nights cycle. The texts of this tale, also known as “Arabian Nights,” are in Arabic, but of a kind that reveals the Arabo-Persian community from which they had sprung. Sindbad is a Persian name, as are many basic terms adopted by Arabic: nakhuda for captain, rahnama for sailing directions for example. Moreover, ongoing archaeological research suggests that the port of Siraf on the Persian coast was in the 9th and 10th centuries among the principal termini of this seagoing traffic, which included luxury ceramics from China.

The decline and fall of the Abbasid caliphate reduced the prosperity and importance of this core of the Islamic Middle East, and there followed a drop in the volume of long-distance trade with the Orient. A revival, however, came with the rise of Europe as an avid consumer of Oriental luxuries, especially spices. Until the end of the Middle Ages, the shippers and traders were the same Arabs and Persians, but a fierce contest for this lucrative traffic opened with the irruption of the Portuguese into the Indian Ocean and the Persian Gulf at the turn of the 16th century. The Portuguese seized, among other places, several ports in the Persian Gulf, of which Hurmuz was the most important. On the Muslim side, the Ottoman Empire made its entry into the arena with the conquest of Iraq and attempts to challenge the Portuguese in the Persian Gulf. Significantly, the Turks failed where the English and Persians succeeded a century later. By then—in 1622—the East India Company had sown the seeds of the British empire of India, and in subsequent centuries the Persian Gulf functioned as one of the two arteries of Britain’s trade with its major colony (the other was the all-maritime route around Africa). Great Britain found it necessary to control the Persian Gulf for this reason, and she successfully strove to establish her dominant position there during the 18th and 19th centuries. In the first decade of the 20th century Britain added a new dimension to her efforts: search for oil. This in turn brings us to the last and most dramatic stage in the history of the Persian Gulf.

A simple enumeration of the countries sharing the Persian Gulf's coasts and waters offers an evocative panorama of contemporary history: Iran, with the longest shoreline and some of the busiest ports along the northeastern coast; Iraq at the head of the Persian Gulf, then Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates, and Oman. All these countries, in varying degrees, are blessed with vast oil reserves lying along the coasts both under the ground on land and below the sea bottom. It is this vital resource that has propelled the Persian Gulf into the limelight of world events, and the story of its discovery, development and struggle over its exploitation makes for fascinating reading. It began almost a century ago, when in 1908 British prospectors struck oil at the Persian site of Suleymaniye. For nearly two generations, until the early 1950s, the province of Khuzistan was the center of production, processing and exporting oil, and the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company had the lion’s share of this lucrative business. Geologists rightly suspected, however, that oil deposits might exist in many other parts of the Persian Gulf area. During the 1930s, a number of finds were made on the Arab side from Iraq all the way to Oman. This time mainly American companies seized the initiative, but until World War II production remained relatively modest. The war and the quickened pace of consumption in the industrial world, especially in the United States led to further development of these sources, but the main stimulus for the sudden and vertiginous development of oil wells on the Arab side of the Persian Gulf came from the drama of Iran’s attempt to acquire a fairer share of its wealth. Great Britain and the United States thwarted Dr. Mossadegh’s heroic struggle, and in the process the production and export of oil from Iran was temporarily halted. That in turn created a windfall for the companies exploiting the oil fields on the Arab side, and their prospectors discovered still more deposits whose yield has led to today’s fabulous wealth of Saudi Arabia and the other principalities along the Persian Gulf